Fortini/Cani (1976)

As part of exploring the context of Moses und Aron (1974) I am exploring Huillet and Straub's other films including this one.

Fortini/Cani (1976) marks the beginning of a new phase for Straub and Huillet as it was their first Italian film. Italy had been the subject and location of some of their previous efforts, most notably Othon (1969) and History Lessons (1972), and even some of the funding for Moses und Aron (1974) had come from RAI, but the works themselves had been predominantly German-funded and usually in the German language.

As a result it becomes the point at which much English language scholarship around Huillet and Straub dries up a little. Roud's book - for over two decades the only English language book on the duo - stops even before the completion of Moses und Aron, the next book in English, Barton Byg's "Landscapes of Resistance" covered only their German period. Whilst I understand Ursula Boser's 2004 "The Art of Seeing, the Art of Listening" is apparently a little more wide-ranging, I've never managed to get hold of it. Ute Holl's "Moses Complex obviously largely focused on Moses und Aron. Recent works such as "Writings" by Sally Shafto, and "Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet" by Ted Fendt have done something to redress the balance but certainly it feels something like dropping off a cliff edge. For me being able to read about Straub/Huillet's work is such a crucial part of watching with it and engaging in it because you tend to need to know so much in advance.

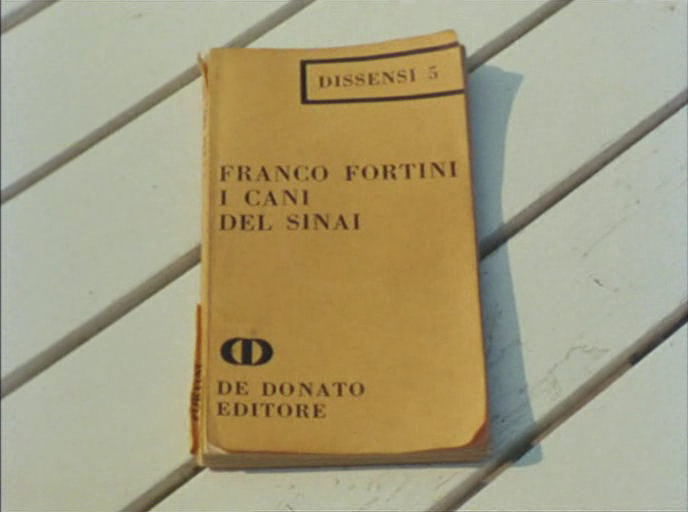

The title, as is often the case, is somewhat unusual. The "Fortini" is the Italian writer Franco Fortini; the "Cani" from the title of his book "I Cani del Sinai" (The Dogs of Sinai), although, as the film concedes early on in proceedings "There are no dogs on Sinai". Having worked on a number of historic texts during the 1970s, the filmmakers were keen to return to the approach of some of their earliest work and adapt text by a living author and Fortini was keen to see his work given similar treatment as that of Heinrich Böll, whose work was the subject of Machorka Muff (1962) and Not Reconciled (1965).

This time, however, the major difference is the appearance of Fortini himself. Fortini appears reading various passages from the work itself. It is left to the audience to decide if this is Fortini appearing as himself, or playing a version himself, or indeed another man of similar age. The lack of clarity on this issue raises a further question of genre: is the film a documentary or something else?

The "something else" in that question summaries the difficulty of pigeon-holing exactly what the film is. Aside from the the scenes of "Fortini" reading two other types of footage dominate. The first consists of Fortini continuing to read excerpts from the book, but as a voiceover, over various scenes of Italian land and city-scapes. In one particularly striking one, the camera holds static down what appears to be a reasonably typical Italian street. Cars drive up and down, people walk along pavements seemingly going about their everyday business. And then I see it, and struggle to believe that I have not noticed it before; Florence's Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore poking out in the background.

In attempting to reflect how I missed such an obvious landmark I can only reflect that this is because of how the film up to this point has trained me to watch it, not only in the scenes of Fortini, but also in the third type of footage - the long, slow, almost silent, 360° pans around various landscapes. Watching these in a cinema is quite unlike watching such images at home on a DVD player. For one thing the there are no distractions. No escapes when otherwise temptation to look away to be distracted might prove irresistible. For another there is the sound, the quietness of crickets in the background, and an audience all holding their breaths. I'm reminded of Kolker's quote about "viewing a film by Straub and Huillet... is essentially an act of watching oneself watch a film" (208). The process is a little like mindfulness, eventually you yield and the rich images, textures sounds are transformative and indeed transportative; they take you to another place. Another quote about Huillet/Straub which I can't seem to shake off is Daniel Fairfax's line about the "sensual role of the material environment in their work". It's the slowness of the panning camera gradually peeling back a little at a time. Because of this you find yourself focusing on the textures of a stone wall, or the expression on a passerby, and somehow missing a cathedral spire poking out magnificently from behind the buildings.

The beauty of the locale is something of a double edged sword, however. Much of the pans across the countryside are taken in the Apuan alps, the scene of the 1944 Vinca massacre of 162 Italian citizens by Nazi soldiers, though Italian fascists were complicit. At times these are left for silent reflection, but at times they are accompanied by Fortini's commentary. The primary theme of Fortini's book is the Six Day War and Israel's seizing of the Sinai Peninsula which Fortini is appalled by. Fortini, who was no stranger to the issue of anti-Semitic abuse on account of his Jewish father,is particularly critical of the way large swathes of Italian society were supportive of Israel. Fortini argues "that the enthusiasm of the Italian intelligentsia of 1967 for the Israeli course was fuelled by the concealment of the Fascist...complicity in the extermination enterprise and by the burying of the victims on Italian soil" (Rancière 41). As in Moses und Aron and numerous other of their films Huillet and Straub are drawing attention to the ground where blood of earlier generations has been spilt even though it is no longer visible. The quiet beauty of the landscape speaks volumes about our attempts to cover our bloody past when it suits us.

There is one particular shot that highlight. There are several shots of landmarks and signs in the film commemorating those who have been slaughtered in the one. This particular shot begins on one such obelisk, before commencing a slow 360° pan around the otherwise quiet location, only then to end on the same plaque. Rather than using historic documentary footage, Straub/Huillet use this subtler approach.

"There are no tortured bodies matching the writers words, but the opposite - their absence, their invisibility. From the terrace where Fortini is rereading his text...the camera slips far away to explore the places where the massacres occurred. In those mute hills, crushed by the sun and deserted villages, only the words of commemorative plaques remember, and say, without showing it, the blood that once stained these oblivious lands." (Rancière 42)In addition to the argument from the Fascist past, Fortini also argues that Italian support for the war derived from anti-Arab sentiment. He argues this at length, and on a single viewing it is difficult to be able to competently summarise it (not least as the subtitles left certain sentences untranslated), but essentially resists the accusation that criticism of Israel is anti-Semitic by referencing his own suffering on account of it and by drawing a sharp line between Israel the state and the Jewish people as a whole. That his points here seem so contemporary given the once again apparent problems of anti-Semitism coming from the resurgent far left of British politics. Fortini feels a sense of isolation, marginalised for being a Jew by the wider society, whilst simultaneously marginalised by other Jews for not being sufficiently pro-Israeli,

There are also allusions to the Hebrew Bible, not least a passage where Fortini talks about reading it in his youth and contrasting "lo scontro esaltante, liberatore, con la scrittura, i Salmi, Giobbe, Isaia, letti e riletti con terrore e rapimento" (the exciting, liberating battle with the Scriptures, the Psalms, Job, Isaiah, read and reread with terror and rapture) with his perceptions of his own faith. There's a lengthy static shot from the balcony in a synagogue whilst various Jewish rituals are undertaken.

As noted above whilst the footage mainly falls into three categories (Fortini reading, silent nature and Fortini reading over images of nature) other such images do appear. For one thing there is the film's opening image (above) of the book itself, followed shortly afterwards from a close up on its dedication. There are also various cuttings from newspapers from various nations including, of all things, one from the Daily Mail. These shots emphasise Huillet and Straub's rootdsness in texts. The film is an adaptation of "I cani del Sinai", but as with Machorka Muff they are happy to go beyond the one text by incorporating 'contemporary' newspaper headlines and articles which they want to hold up to criticism.

However the film goes beyond the text in other ways. The screening notes from the showing I attended consisted of Fortini's 1978 "Note for Jean-Marie Straub" that accompanied the 2013 English translation of the book (which rumour has it includes a DVD of this film). In it it is clear that Fortini recognises that Huillet and Straub have brought out things from his work which he himself was not aware of until he watched the film. "Through the gaze of the camera looking at me, I was also able better to understand some formal lessons I had received, across many years" (Fortini). He goes on to explain how the instructions from Straub and Huillet worked by "unweaving the fabric of my thoughts, surpassed them and conserved them" (Fortini). The excerpt ends "From then onwards the words and ideas which, in "The Dogs" still pained me have ceased to hurt me (Fortini).

=========

- Fairfax, Daniel (2009) "Great Directors: Straub, Jean-Marie & Huillet, Danièle", Sense of Cinema, September. Available online

https://sensesofcinema.com/2009/great-directors/jean-marie-straub-and-daniele-huillet/

- Fortini, Franco (2013) "A Note for Jean-Marie Straub" in Fortini, Franco The Dogs of the Sinai, translated by Alberto Toscano. Seagull Books

- Kolker, Robert Phillip (1983) The Altering Eye: Contemporary International Cinema. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rancière, Jacques (2014) Figures of History. John Wiley & Sons

Labels: Other Films, Straub/Huillet